The OMNIBUS Directive is a set of texts designed to strengthen consumer protection against misleading or unfair commercial practices.

It came into force in 2019 under European law. It was transposed into French law by Ordinance no. 2021-1734 of 22 December 2021, which came into force on 28 May 2022.

In 2020, the Conseil National de la Consommation (CNC), a consultative body chaired by the Minister for Consumer Affairs, had the good idea of consulting Revenue Management experts to gain a better understanding of the issues involved in Yield and dynamic pricing in particular, prior to the transposition into French law. And in its wisdom, this same CNC had the good idea of asking N&C to be one of the experts consulted.

There are a number of key points to remember about this OMNIBUS directive:

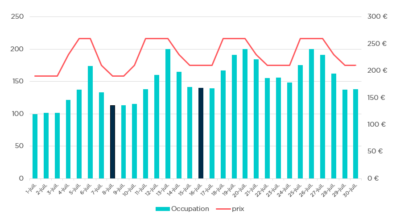

Dynamic Pricing

The principle of « Dynamic Pricing », which is present in the European text, has not been transposed and there are no specific regulations governing its practice as such, despite the opinion of N&C and our consulted colleagues.

Seasonal prices

For those of you who are worried and who have told us so, rest assured that having seasonally adjusted prices, i.e. different prices for different dates of stay, is not prohibited by the Omnibus Directive. The practice of cross-bar pricing is regulated, but it involves looking at the price history for a given date of stay, not comparing the prices for one date of stay with those for previous dates.

Price display

Article 2 tightens up the conditions for displaying prices during promotions, particularly with regard to the misuse of crossed-out prices. The legislator now requires the reference price to be « the lowest price charged by the trader to all consumers during the last thirty days prior to the application of the price reduction ».

The idea is to prohibit the barring of prices that have been artificially increased in the recent past, since there is a suspicion that the price increase was merely a false pretext used to obtain a discount on the new high price.

There are two exceptions to this rule:

- The text states immediately afterwards that « [this provision] does not apply to price reduction advertisements for perishable products threatened by rapid deterioration », without specifying these concepts. For at least 30 years, the public authorities have considered a week’s mobile home rental, a plane ticket or an overnight stay in a hotel to be perishable products, authorising tourism professionals to freely offer discounts of all kinds. However, it would seem that the notion of rapid deterioration is, in the spirit of the law, reserved for everyday foodstuffs (yoghurt, fruit, etc.). So the use of crossed-out prices does fall within the scope of the Yield law.

- Article 6 bis of the European Directive stipulated that Member States could provide for the case of progressive Early Booking, without designating it as such: « Member States may provide that, where the price reduction is progressively increased, the previous price means the price without reduction before the first application of the price reduction ».

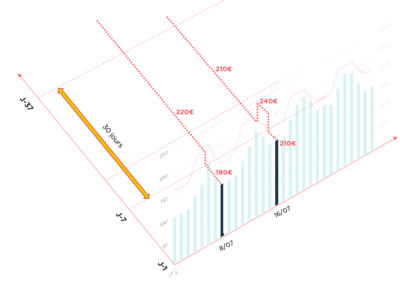

Prices for a given date of stay do not have to be compared with prices for stays over the previous 30 days. For example, we never compare the price of a night on 16/07 (€210) with that of 8/07 (€190).

You could, for example, offer a discount on 16/07 from €210 to €200, regardless of the €190 price on 8/07. Prices can be seasonalized, which is not contrary to the Omnibus Directive.

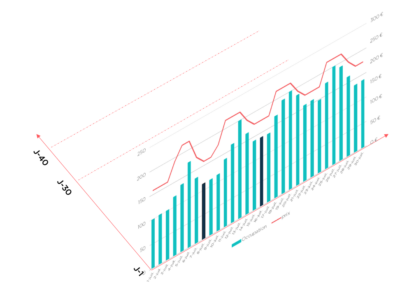

For each date of stay, the Omnibus Directive requires us to look at the price history over the last 30 days.

On the 8/07 date, the price drops from €220 to €190 on D-7. The price can be crossed out: €220 to €190 because the cheapest price in the last 30 days was indeed €220.

But on the date 16/07 with a price reduction to D-7, the price cannot be displayed: 240€ to 210€ because the cheapest price in the last 30 days was 210€ and not 240€.

Here is an extract from Article 6 bis (European Directive):

- Any advertisement of a price reduction shall indicate the previous price applied by the trader for a specified period before the application of the price reduction.

- The previous price means the lowest price applied by the trader during a period of not less than thirty days prior to the application of the price reduction.

- Member States may provide for different rules for goods which are likely to deteriorate or expire rapidly.

- Where the product has been on the market for less than thirty days, Member States may also provide for a shorter period than that provided for in paragraph 2.

- Member States may provide that, where the price reduction is gradually increased, the previous price means the price without reduction before the first application of the price reduction.

Here is the extract from the transposition of Omnibus into French law, published in the Journal Officiel (Ordinance No 2021-1734 of 22 December 2021 transposing Directive 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on better enforcement and modernisation of EU consumer protection rules):

After article L. 112-1 of the same code, an article L. 112-1-1 is inserted, worded as follows:

« Art. L. 112-1-1. – I. – Any advertisement of a price reduction shall indicate the previous price charged by the trader prior to the application of the price reduction ».

« This previous price corresponds to the lowest price charged by the trader to all consumers over the last thirty days prior to the application of the price reduction ».

« By way of exception to the second paragraph, in the event of successive price reductions over a given period, the previous price is that charged before the first price reduction was applied ».

Some companies use progressive Early Booking. This exception mentioned in Article 2 is made for them. It is an Early Booking valid by definition from the opening of sales, with a progressive succession of discounts. For example: -30% until D-180, then -20% until D-120, then -10% until D-90. In this scheme, the crossed-out price remains authorised in relation to the public price as it will be when the Early Booking expires. This is the case even if, at any given time, the lowest real price displayed over the last 30 days is not this reference public price, precisely because of the progressive nature of Early Booking.

Transparency of prices

Article 6 provides a more detailed framework for the information to be given to the customer on the understanding of the price in the case of a « personalised » price: « The trader shall provide the consumer with the following information in a legible and comprehensible manner (…): the application of a personalised price on the basis of automated decision-making, where applicable (…) ».

This scheme is not in contradiction with Dynamic Pricing, which is not a « personalised » price, but on the contrary a price variation practice that applies to the greatest number, and in particular to all direct sales customers.

On the other hand, if a price is constructed on the basis of customer profiling (age, internet purchase history, etc.), resulting in a different price for Jacqueline than for Paul for the same product, purchased at the same time, then the price proposal algorithm must be explained. It should be added that this isn’t necessarily a good pricing practice. Pricing is aimed at well-defined demand segments, not at individuals according to their own profile.

Misleading practices

For the rest, and in a less restrictive way, the Consumer Code and the Tourism Code continue to apply to all accommodation businesses (HPA, hotels, tourist residences, etc.), prohibiting misleading or unfair practices and requiring certain price information.

As a result, the prices of all services, including taxes, must be clearly and legibly displayed at the entrance to each establishment. Prices are free but must be displayed. Not necessarily the price of the day, but for example the minimum and maximum prices for the season.

Another example of a misleading practice to be banned is that of false opinions: Article 3, paragraph 28, stipulates the following prohibition: « (…) disseminating or having disseminated by another legal or natural person false opinions or false consumer recommendations or modifying consumer opinions or recommendations in order to promote products ».

This is common sense, but the legislator is right to specify it.

Finally, without specifying what is « reasonable », the Consumer Code, in Section 1: Unfair commercial practices, sets out the following prohibition in Article L121-4:

« To offer the purchase of products or the provision of services at an indicated price (…) for a period and in quantities that are reasonable given the product or service, the extent of advertising for the product or service and the price offered ».

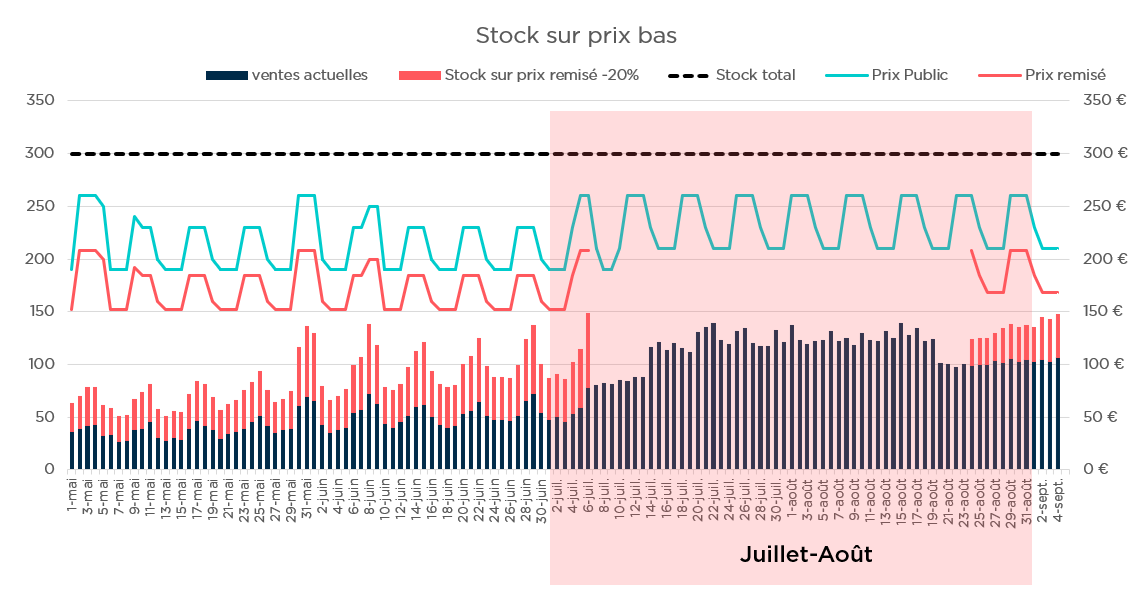

This applies in particular to tempting discounts with quantities that are too limited. Advertising « from €199 » or « incredible offer of up to 50% off » and offering only 2 holidays at these price or discount levels is deceptive. Case law seems to indicate that « reasonable quantities » are deemed to exist when the promotional or low-price stock represents around 10% of the total stock.

In the example, a strong communication such as « exceptional 20% off offers from 1st May to 4th September on a selection of dates » is valid, as 11% of stock is on special offer.

On the other hand, a strong communication saying « -20% on a selection of dates in July-August » isn’t valid because only 4% of stock is on special offer.

Conclusion

The Omnibus law goes some way towards cleaning up practices, without prohibiting the practice of Yield Management. This is a good thing.

Prices can be seasonalised, they can be subject to dynamic pricing, and Early Booking of all kinds can be used.

However, beware: the DGCCRF has departmental offices that may interpret the legislation differently from one department to another. We have received feedback from the field on cases of different interpretations by the DGCCRF during checks on the display of prices at campsites. The two departments concerned made different recommendations (for one, the minimum and maximum prices were sufficient; for the other, the daily price had to be displayed).

Keywords: OMNIBUS law, OMNIBUS Directive, consumer protection, misleading commercial practices, European law, transposition, Order, Conseil National de la Consommation, experts, Revenue Management, Yield, dynamic pricing, European Directive, Progressive Early Booking, dynamic pricing, seasonal prices, price display, promotions, crossed-out prices, consumer code, tourism code, accommodation, misleading practices, price information, false advice, unfair practices, case law, DGCCRF, controls, campsites.